A signature concept in Eckhart Tolle’s New Age bestsellers is the notion we carry a “pain-body” within: a “semi-autonomous energy form” amassed from our past emotional suffering. The pain-body is said to bring misery—generating and feeding on emotional suffering. Tolle directs readers to break free from its psychic grip and “dissolve” it. But how original is this idea? Here I argue many characteristics find precedence in works by lesser-known authors. The first is Fourth Way teacher Maurice Nicoll, a former protégé of the famous psychologist Carl Jung, who wrote of a psychological “time-body”. Ideas Nicoll presented later converged in the work of the underground independent teacher Barry Long—whose London seminars Tolle attended—into a concept near-identical to that in Tolle’s later work. This deep dive into the hidden history of influence behind Eckhart Tolle’s “pain-body” reveals the concept is less unique than many may think.

Of all contemporary authors advocating present-moment awareness or mindfulness, Eckhart Tolle is by far the most popular. In fact, he might be the most popular modern author in today’s broader “spirituality” genre. He has topped the New York Times bestsellers list, sold tens of millions of book copies worldwide, and is consistently ranked by Watkins Review alongside the Pope and Dalai Lama as one of the most spiritually influential people in the world. [1] But what can be said about the originality of his work?

In a previous article, I looked at how present moment awareness practice became popular in the West in the late 20th century. I highlighted parallels between the modern mindfulness movement, which hit the mainstream in the 90s, and the work of Eckhart Tolle, who was “catapulted to ‘bestseller-dom’ by the phenomenally popular daytime talk show host Oprah Winfrey’s enthusiastic endorsement of his work” in the 2000s.[2] [3]

I compared these perspectives to those advanced earlier by the Fourth Way tradition initiated by the enigmatic G.I. Gurdjieff—a globetrotting mystic from Armenia. This esoteric tradition was introduced to the West in the early 1920s, although Gurdjieff said it had very ancient roots.

To briefly reiterate, a central Fourth Way idea is the pursuit of self-development through “waking up” in daily life via the practice of self-remembering and self-observation. This involves bringing one’s conscious attention to the present moment and observing, impartially, how one reacts psychologically and behaviourally towards life’s varied situations. It is a methodology for self-knowledge and inner change.

While awareness or mindfulness exercises have long existed in Eastern religions, they were probably articulated accessibly and systematically throughout the contemporary western world for the first time by teachers of the Fourth Way. However, being esoteric in nature, this tradition did not gain or really seek mainstream popularity—and its philosophy arguably precluded this.[4]

The Fourth Way emphasizes practicing awareness primarily within the events of ordinary daily modern life—rather than formal practice settings or retreats, as was often the case with Eastern contemplative exercises. Gurdjieff believed it was in life’s everyday situations where effecting a shift in consciousness was most important. The approach he advocated was a precursor to later 20th century sources that encouraged awareness or mindfulness in everyday life. Among these, Tolle is easily the most prominent.

It’s no secret that many of Tolle’s ideas are not new in themselves—a fact Tolle himself seems to recognise at times. In The Power of Now, he suggests his work is a modern expression of perennial wisdom, “a restatement for our time of that one timeless spiritual teaching” which is “the essence of all religions.”[5] At its core is present-moment awareness, commonly called mindfulness today, although Tolle does not use that term. And it’s certainly true that this practice, state, or way of living, however it is described,[6] is not new.

Nonetheless, Tolle’s direct, clear and modern writing style combined with his universalist mysticism stripped of religious or moral obligations, makes his work more accessible and perhaps palatable to modern “spiritual but not religious” tastes, which often shun commitment to any creed, instruction or obligations. But in the process of presenting spiritual ideas in “a clean contemporary bottle”[7] Tolle also downplays, in my view, the difficulties faced and discipline required with this kind of practice, which are major themes typically found in prior sources, including the Fourth Way. This no doubt adds to the appeal of his work today—although, in my personal opinion, not without cost.[8]

Eckhart Tolle (left) with the Dalai Lama at the Vancouver Peace Summit, September 2009

Nevertheless, Tolle’s modern, accessible style and approach in presenting present-moment practice, and his particular emphasis on certain psychological changes produced by it, still owes much to the Fourth Way I believe—particularly its exposition by Maurice Nicoll—and far more so than to older, more traditional religious sources. Readers can refer to my previous article “The Creation of Now: How Fourth Way Authors Sparked a Revolution of the Present Moment” for more on this.

But what about Eckhart Tolle’s pain-body? Tolle presents the pain-body in conjunction with the more common notion of the personal ego identity as a “false self” to be liberated from. The pain-body is “the emotional part of the dysfunctional ego”[9]—its “dark shadow” according to Tolle.[10] Those familiar with this kind of literature would know that references to a false egoic identity or self, to be transcended via some kind of self-realisation process, are not uncommon. [11] The early 20th century Hindu teacher Ramana Maharshi, whom Tolle speaks very highly of, defines the ego in much the same way as Tolle. The Fourth Way’s “False Personality” or “Imaginary I” has much the same meaning and is described as a “False Self” by Nicoll as well.[12] And Buddhism also regards the ego as an “erroneous conception of the ‘self.’”[13]

Yet while Tolle’s conception of the ego may be a more common spiritual or psychological idea, the “pain-body” still stands out as somewhat novel. Arthur Versluis, an author and professor of religious studies, writes that while many of Tolle’s ideas derive from older traditions, synthesized into a light contemporary style, “Tolle does develop his own individual concepts, like the notion of a ‘pain-body’ that we carry about with us.”[14] And I think this reflects how most readers, who view Tolle’s work with an eye to other sources, would regard the pain-body. It is by far the most prominent feature in his work that cannot readily be found elsewhere. But that does not mean precursors do not exist; they are just unfamiliar to most. The relative obscurity of these sources makes it quite understandable that the pain-body could be misperceived as a unique idea. Certainly the correlations I will highlight would be unknown to the majority of Tolle’s readers. Yet their existence nevertheless shows that Tolle’s pain-body notion is not very original after all.

To briefly summarise the concept, Tolle claims almost everyone carries a “pain-body” within, consisting of the “remnants of pain left behind by every strong negative emotion” experienced. This residue of “accumulated pain” forms an inner “energy field of old but still very much alive emotion” existing within us, which is “the living past in you.” People carry pain bodies of greater or lesser density or heaviness according to how prone to negativity or burdened by past emotional pain they are. This “emotional pain-body” renews and replenishes itself with every unconscious experience of further emotional pain, and deliberately generates negative emotions and thoughts to feed, grow and sustain itself. Tolle tells his readers to consciously observe the pain-body in action and disidentify from the influx of negative thoughts and emotions it produces; in this way it loses strength and can be “transmuted” by one’s “conscious presence”. The endgame is to dissolve it entirely by this method of detached conscious attention in the Now.[15]

The pain-body concept is closely connected with present-moment practice I have been discussing, as Tolle portrays this as the main way to deal with it. But while his method here is broadly traceable to the self-observation practice of the Fourth Way, the psychological object is more specific and distinctive in Tolle’s case.

In Gurdjieff’s teachings, self-observation of habitual thoughts, emotions, reactions and negative states is paramount, but there is no “pain-body” as such claimed to be behind them.[16] Nevertheless, as with certain other aspects of Tolle’s work I have looked at, the pain-body concept does find precedence in sources linked to Gurdjieff. The first author I’ll examine, Maurice Nicoll, operated within the Fourth Way system, while the other, Barry Long, operated outside of it, but both elaborated ideas which are analogous to the pain-body in important ways.

Dr Maurice Nicoll (1884-1953) was a Fourth Way teacher whose work, I have been arguing, has wider significance and influence than is generally recognised. I trace and identify pain-body precursors in two concepts he discusses.

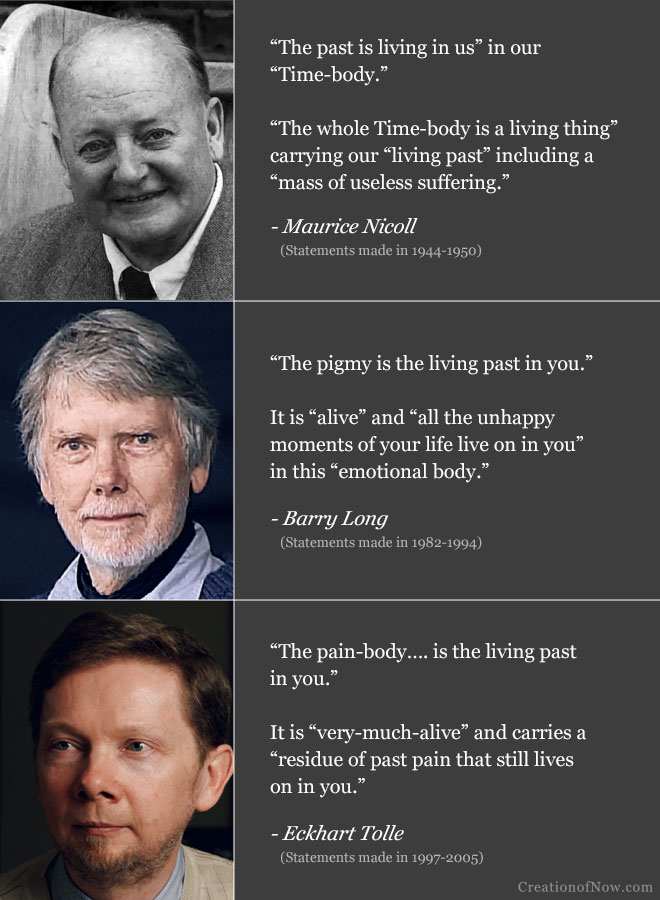

To summarise, Nicoll tells us “the past is living in us” through our “time-body” which stores and carries “a mass of useless suffering” in us due to our frequent absorption in negative emotions. Our negative Time Bodies must be cleansed and “transformed” by “living more consciously now” and observing and ceasing to identify with negative emotions as they occur. This idea certainly bears comparison to Tolle’s pain-body concept. As do Nicoll’s discussions of the “negative part of the emotional centre”—a psychic infection that, by his telling, grows and feeds on negative emotions and thoughts which it expresses and generates. Much like the pain-body, this too must be entirely eradicated through conscious observation and deliberate non-identification with its psychic activities.

Next, I’ll show how these two antecedents converge in the work of Barry Long (1926-2003), an underground independent teacher whose seminars Tolle attended in London before his own teaching career began. As we shall see, Barry Long’s descriptions of the “unhappy body” within the human psyche, combines many attributes of the two components Nicoll described into one. Long’s “unhappy body … composed entirely of … painful emotional material”—and also called the “emotional body” and, strangely, “the pigmy” at times—is conceptually near-identical to Tolle’s “emotional pain-body.”

There are numerous correlations between Nicoll, Long and Tolle’s work in this area which I’ll outline. These correspondences strongly suggest that Nicoll and Long decisively informed Eckhart Tolle’s latter presentation of his standout “pain-body” concept.

The Time-Body and Pain-Body as Carriers of Negative Emotion

The time-body is a supplemental concept in Fourth Way teachings. Purists might not see it as part of the system proper. In a guidebook to Gurdjieff’s key concepts by Sophia Wellbeloved, the time-body is not listed.[17] This is no doubt because it was not introduced by Gurdjieff, the system’s originator, but his most famous pupil, P.D Ouspensky. It was never universally adopted, and apparently used sparingly where it was. The term’s low-profile within this tradition, already obscure to many, may explain why its connections to Tolle’s pain-body are not widely recognised.

Ouspensky was a writer of some renown on esoteric topics before he met Gurdjieff in Moscow, and referred to the “time-body” before he was familiar with Gurdjieff’s Fourth Way system. The term appears in his 1912 book Tertium Organum, concerning the metaphysics of space and time. This book met some acclaim in his native Russia and, later, the English speaking world, after it was translated and published in America (without his knowledge initially, as he was then preoccupied with fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution). Ouspensky’s prominence prompted Gurdjieff to make contact with him in 1915.[18] The result of this is narrated in Ouspensky’s classic book In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, which recounts his time with Gurdjieff studying his system.

But Tertium Organum came earlier, and in it Ouspensky used the term “time-body” when discussing multidimensional cosmology. He holds that every physical body moves in the fourth dimension of time as well as space and has a time-body in addition to its three-dimensional form. Like time itself, this body in invisible to our senses and yet is very real.[19] He only used the term once, but discusses similar notions with other terms.[20] However, he did not invest the concept with the psychological meaning it would later acquire in the Fourth Way.

Ouspensky later referred to the time-body when teaching the Fourth Way, but it still appears rarely in his literature.[21] However, one can gather he employed it in his informal talks from time-to-time, which made an impression on his most important pupil, Dr Maurice Nicoll, [22] who uses it more than 40 times in his Psychological Commentaries on the Work of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. This extensive volume focuses primarily on the practical psychological component of Fourth Way teachings, often referred to as “the work.”

Nicoll, a one-time protégé of famous psychologist Carl Jung, put his rising psychiatry career on the backburner in 1922 to dedicate himself to studying and later teaching the Fourth Way. He studied with both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, and taught the system independently from 1931, at Ouspensky’s request. It is in Nicoll’s iteration of the teaching, which incorporates Ouspensky’s notions of time and recurrence, among other influences, where the time-body takes on meanings comparable to Tolle’s pain-body.

Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries is a lengthy five-volume corpus, however, so it’s easy for the significance of the idea to be overlooked when so much else gets more attention. But it’s how he uses it that matters here, not how often. Nicoll not only describes the time-body as something like a body we possess for the “invisible fourth dimension” as Ouspensky did.[23] He develops it further, describing the time-body as something like a psychic accumulator and carrier of past emotional negativity and suffering—and here the idea takes on a number of characteristics latter appearing in Eckhart Tolle’s pain-body.

It’s worth noting that the terms themselves share a similar construction: both are three-syllable compound nouns that modify the word “body.” And in both cases, these bodies cannot be seen with the naked eye, but are held to exist psychically nonetheless. However, the conceptual commonalities run much deeper. Look closely, and they become obvious.

Nicoll suggests that our inner states and memories “remain in the Time-Body.” So if you “enjoy your negative emotions” then your Time-Body will be “in a bad state” from being “full of negative emotions”. Since most of us wallow in emotional suffering, we carry a “mass of useless suffering stored up in our Time-Body.” However, the time-body’s overall state can be better or worse depending on how prone to negative emotions we are. A particularly “negative” time-body, he writes, “is a bad kind of time-body to have.” [24]

Tolle similarly claims that “every strong negative emotion that is not fully faced” will leave behind “remnants of pain” in the pain-body, which carries “accumulated pain” from “every emotional pain that you experience.” Since most humans have an “addiction to unhappiness,” most pain bodies carry a significant weight of emotional pain. But each person’s pain-body will be more “dense” or “heavy” according to their attachment to emotional negativity.[25]

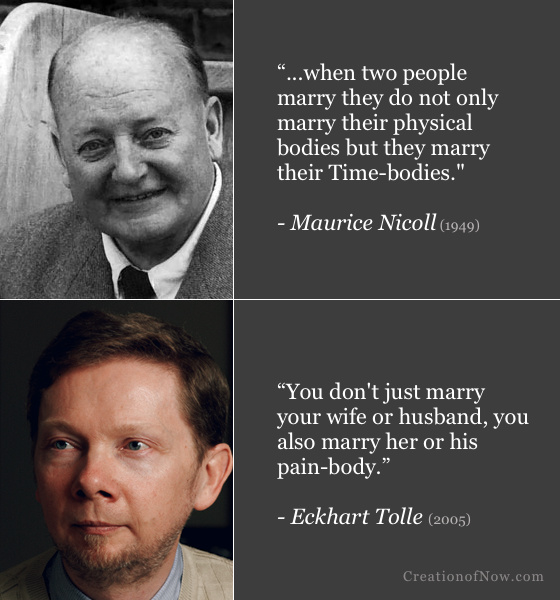

Quite interestingly, both authors make corresponding points about the adverse effects these psychic bodies have on marital life—when they are too “negative” or “dense” respectively. Nicoll writes that “when two people marry they do not only marry their physical bodies but they marry their Time-bodies.” A marriage “will not be so beautiful as romance paints it” if one’s spouse looks “wonderful but has a negative Time-body” he warns.[26] Tolle similarly claims, “You don’t just marry your wife or husband, you also marry her or his pain-body.” A partner’s “excessively dense” pain-body is also liable to thwart marital bliss, typically unleashing its “intensely hostile energy” sometime “after the honeymoon”. “It would perhaps be wise to choose someone whose pain-body is not excessively dense,” Tolle cautions.[27]

Another commonality is that both authors connect their respective bodies with the past and suggest they are alive—and that the past itself lives within us through them. Nicoll tells us the time-body is a “living thing” and suggests that through it we are connected with a “living past” and “the past is living in us.”[28] Tolle also holds that the pain-body is “very-much-alive,” is an “energy-form that lives,” and tells us, “It is the living past in you.”[29]

Their method to transform or transmute these respective bodies is also much the same. One can “transform the Time-body,” Nicoll maintains, by living “more consciously now” and “observing when you take situations in life negatively” and ceasing to identify with your typical reactions. This allows the light or force of consciousness to change the time-body.[30] Tolle similarly directs the reader to observe or witness the pain-body—which can be seen as “a heavy influx of negative emotion when it becomes active”—in order to stop identifying with its negativity and thereby “transmute” it with your conscious presence.[31]

So in summary, each psychological body stores up and carries emotional pain or suffering from the past, is more negative or dense according to how much of this it carries, is alive, contains the “living” past, and can be transformed or transmuted through the conscious observance of emotional negativity in the present moment—and ceasing to identify with this. Furthermore, Nicoll and Tolle both tell us that we marry our partner’s time-body or pain-body, for better or worse.

But there is an important difference. To Nicoll, the time-body is not negative in itself, just made that way by all the emotional suffering it has become stored and swamped with. It is to be cleansed, not eradicated. The pain-body, however, is essentially negative. It doesn’t just accumulate the energetic “residue” of painful, negative emotions, but is actually formed of this substance. It serves no useful or neutral purpose and can and should ideally be dissolved entirely, according to Tolle.

But it’s these distinguishing features, among others, where the pain-body does share much in common with another concept Nicoll elaborates at length: the “negative part of emotional centre.”

A Negative Psychic Infection Within

The Fourth Way stresses that negative emotions, aside from basic survival instincts, are unnecessary and have no natural place in the human psyche. Nevertheless, they are prevalent. We are said to be infected by emotional negativity pervading our environment from birth. Consequently, during childhood our “emotional centre”—the seat of emotions in the psyche—is altered from its natural state, forming an artificial part to express this negativity. Ouspensky outlines the idea as follows:

All our violent and depressing emotions and, generally, most of our mental suffering has the same character—it is unnatural, and our organism has no real [natural] centre for these negative emotions; they work with the help of an artificial centre. This artificial centre—a kind of swelling—is gradually created in us from early childhood, for a child grows surrounded by people with negative emotions and imitates them.[32]

Nicoll refers to this aberrant creation as “the negative part of the Emotional Centre”—a term Gurdjieff is recorded using just once in Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous.[33] Nicoll tells us Ouspensky “especially emphasized” this idea when imparting Gurdjieff’s system and brought “the study of negative emotions … into the foreground.” [34]

But there is far more about “the negative part of Emotional Centre” [35] in Nicoll’s extensive Psychological Commentaries than in Ouspensky’s written work, not to mention Gurdjieff’s. Nicoll not only brings this concept into focus, but shares some novel insights about it. Much that he conveys finds commonality with Tolle’s pain-body. Some similarities overlap conceptually with the time-body, while others are quite distinct.

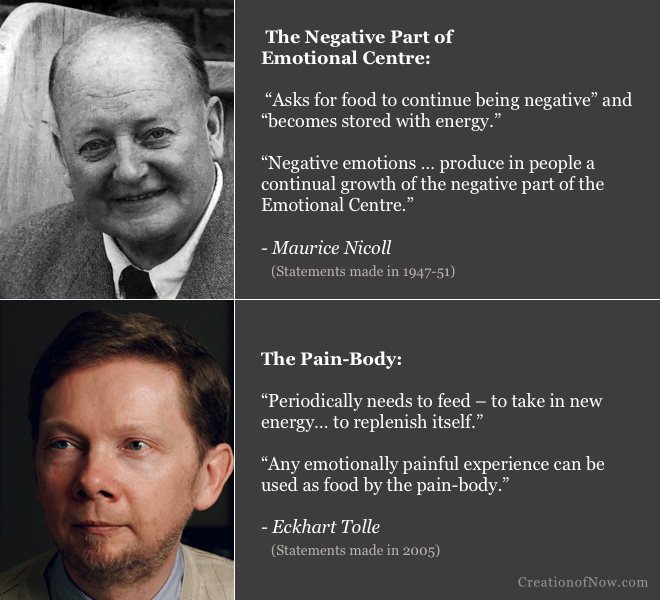

To summarize the general idea, Nicoll tells us “the negative part of the emotional centre” forms within us during childhood under the influence of the emotional negativity we are exposed to. He likens it to a psychological disease or infection that continues growing throughout one’s life, becoming the primary source of negative emotions and unhappiness in people. This “negative emotional part” feeds on the energy of negative states and also “becomes stored” with this energy, which it uses to produce more negative emotions that will nourish it. This negativity may attack others or oneself. It may be roused into activity by unpleasant events or people, making one react negatively, or by one’s own habitual negative thoughts; likewise, the negative emotions it produces give rise to and reinforce negative thinking. Much of its functioning is associated with grievances about the past and perceived slights to one’s “false personality”—the false identity we cling to. To reduce its power one must act with more consciousness in the moment and observe and cease identifying with negative thoughts and emotions as they occur—this means one observes them as being separate from oneself, without taking these states to be who we are. This non-identification with negative states starves this part of the negative energy it feeds on and accumulates. Ultimately it can and should be completely “destroyed in us” by this method of self-observation and non-identifying.

These characteristics, among others, closely align to how Tolle would later convey the pain-body concept. I’ll now compare some of these similarities in closer detail.

Growth and Expression from Childhood into Adulthood

Nicoll and Tolle similarly describe of how the negative emotional part or pain-body grows and develops from childhood into adulthood.

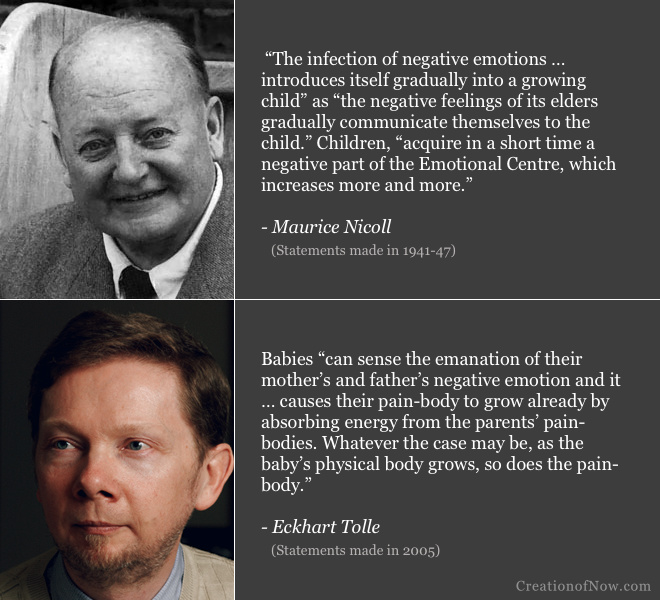

Nicoll claims children “inhale the atmosphere of those around them from birth” who are generally “negative and governed by negative emotions.” Since almost all adults are “deeply under the power of negative emotions” to an extent, the “infection of negative emotions … introduces itself gradually into a growing child” as “the negative feelings of its elders gradually communicate themselves to the child.” As a result, children “acquire in a short time a negative part of the Emotional Centre, which increases more and more” as they grow up.[36]

Tolle also suggests the pain-body exists, in large part at least,[37] “because of certain things that happened in the past,” namely “emotional pain suffered in one’s own past,” which “includes the pain suffered as a child, caused by the unconsciousness of the world into which you were born.”[38] Children “absorb” negative emotional energy from their parents—whose “psychic toxicity is absorbed by the children and contributes to the development of their own pain-body,” resulting in children taking on the negative attributes parents feel, like fear.[39] Babies “can sense the emanation of their mother’s and father’s negative emotion,” he explains, which “causes their pain-body to grow already by absorbing energy from the parents’ pain-bodies. Whatever the case may be, as the baby’s physical body grows, so does the pain-body.”[40]

Both authors relate how children soon begin to exhibit negative emotions and behaviour due to the increasing presence of these psychic growths. “After a time the child begins to shew negative emotions,” Nicoll explains, much like those of the “parents, teachers, and all those [it was] brought up amongst,” and will “sulk and brood and nag and feel sorry for itself and so on.”[41] Tolle likewise describes how the presence of a child’s pain-body may “manifest as moodiness or withdrawal,” so that it “becomes sullen, refuses to interact, and may sit in a corner” or has “weeping fits or temper tantrums”. This may be “a reflection” in the child of the emotional pain of its parents, which the child has “taken on… from his or her parents’ pain-bodies.”[42]

Unfortunately, the growth process does not stop in childhood. Even though emotional negativity is unnatural—a claim both make[43]—once entrenched, this negative emotional apparatus keeps developing through the ongoing experience of negative or painful emotions. In this respect it is a psychological “disease” according to Nicoll; a “psychic parasite” to Tolle. As Nicoll tells it, this aspect continues to grow throughout a person’s life by “the continual expression of negative emotions,” which “produce[s] in people a continual growth of the negative part of the Emotional Centre.” [44] Likewise, negative emotional experiences later in life are also said to merge into and add to the pain-body according to Tolle: “It consists not just of childhood pain,” he writes, “but also painful emotions that were added to it later in adolescence and during your adult life.”[45]

Nicoll and Tolle describe these psychic appendages as the primary source of emotional misery in life, and provide similar catalogues of negative states they produce. The negative emotional part is “the seat of negative emotion” and “inner source of negative emotions and general unhappiness,” in people, according to Nicoll. It gives rise to states of “violence and destruction,” hatred, fear, suspicion, resentfulness, self-pity, depression and various “evil and negative emotions.”[46] Comparably, “Any sign of unhappiness in yourself” may be an indication of the pain-body’s active influence, Tolle suggests. States associated with it include: “anger, destructiveness, hatred … violence,” “self-pity, or resentment,” “a desire to hurt, rage, depression … and so on.”[47]

Functionality

Nicoll and Tolle similarly describe how the negative emotional part or pain-body function.

Negative emotions are experienced “whenever [the] acquired negative part of the Emotional Centre is active” in us, Nicoll writes. It can be spurred into activity by habitual negative thinking and reactive attitudes towards life’s events. This will “rouse the negative part of emotional centre with all its endless miseries.” And since “most people are simply swamped by everything that happens to them,” it means “the negative part of Emotional Centre grows and grows” throughout their life.[48] Similarly, “the pain-body has a dormant and an active stage” for most, Tolle writes, and can be noticed “as a heavy influx of negative emotion when it becomes active.” Potentially “anything can trigger it”—such as “negative thinking” or “reactivity” towards any event or other people’s behaviour. Since most people suffer from the “addiction to unhappiness” it perpetuates, then unconsciously their “thinking and behavior are designed to keep the [emotional] pain going” in their lives.[49]

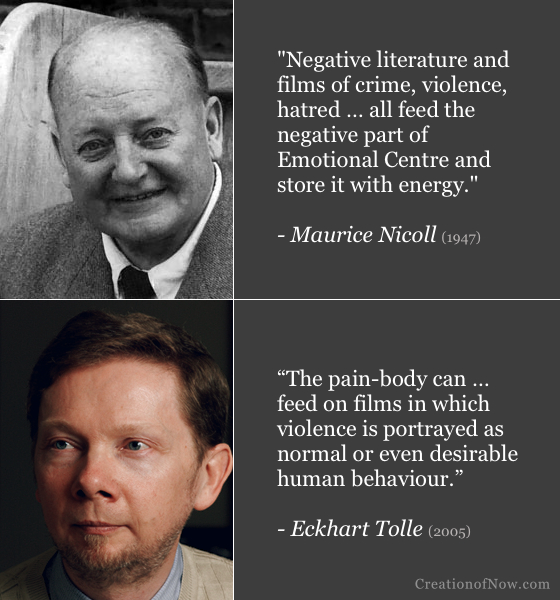

Both psychic interlopers are depicted as craving and seeking what enables them to feed and grow. Nicoll describes how the negative emotional part seeks out energy it can store, feed and grow upon. It “asks for food to continue being negative,” and “if you allow it to feed on negative things, it will grow and grow.” When you “are alone or no one is looking,” he indicates, it can be fed just by “negative thoughts” which “increase the material for making negative emotions.” Negative thoughts, reactions and emotions are not all that can feed it, however. Nicoll claims “negative literature and films of crime, violence, hatred, etc.” will “if identified with, all feed the negative part of Emotional Centre and store it with energy.”[50]

Eckhart Tolle’s pain-body is also said to get “hungry” and seek out the negative energy it “needs to feed” upon. It gets “its ‘food’ through you” from “any emotionally painful experience” or “negative thoughts” that provide “energy … compatible with its own,” Tolle maintains. Even if “you live alone or there is nobody around at the time,” then “the pain-body will feed on your thoughts” which become “deeply negative” under its influence and will be accompanied by a “dark and heavy mood”. Similarly, “the pain-body also renews itself vicariously through the cinema and television screen,” and will “feed on films in which violence is portrayed as normal or even desirable” and any “entertainment” that “fuels the human addiction to unhappiness” by “generating negative emotion in the viewer.” [51]

A well-fed negative emotional part, or pain-body, will bring similar results, which can include violence. Nicoll explains how the “negative emotional part” will “discharge itself on anyone from a trifling cause—i.e. one will become violent over nothing.” As a person “stores up material … for the manufacture of negative emotions” these emotions “sooner or later will wish to rush forth and attack someone and hurt them” or alternatively will “attack oneself” if “they cannot attack others.” “All negative emotions,” he explains, ultimately “desire to hurt, and at the bottom of them are unlimited forms of violence.” [52]

In a similar vein, Tolle tells us that even “the most insignificant event” or an “innocent remark made by someone close to you” can activate the pain-body when it wants to feed. “Once the pain-body has taken you over, you want more pain” and so “want to inflict pain … suffer pain, or both.” “Some [pain-bodies] are physically violent; many more are emotionally violent. Some will attack people around you or close to you, while others may attack you, their host,” he writes. He points out that all pain bodies ultimately “feed on violence, whether emotional or physical.”[53]

Nicoll conveys how an almost constant automatic process of negative emotional re-infection can occur between thoughts and the negative emotional part. While negative thoughts can rouse negative emotions in a person,[54] negative emotions also “bring into operation” more negative thinking[55]—or inner talking, as he calls it—which can produce a “perpetual secret grievance that may spread over and darken all one’s inner life.”[56] The negative emotional centre can induce a “current of lies” that takes over the mind.[57] A key sign and feature of the negative emotional part working, he indicates, is that its activity is “self-running” [58] and can be kept going by mere “thought or memory or imagination” that “goes on and on by itself” which then “feed[s] negative emotions strongly” so that these “go on and on.” [59]

Tolle comparably holds that the “usual pattern” is that emotions arise in reaction to thought, but that pain-body emotions can also generate thoughts that in turn spur on negative emotions. So when the pain-body is active, he advises to check whether “your mind is holding on to a grievance pattern such as blame, self-pity, or resentment that is feeding the emotion.” If the pain-body “gains control of your thinking” and you are “totally identified with whatever the [mental] voice says,” such that your “train of negative thoughts” does not stop, then “a vicious circle becomes established between the pain-body and your thinking” where “every thought feeds the pain-body and in turn the pain-body generates more thoughts.” [60]

Connection to the False Personality or Ego Self

I mentioned before how the negative part of emotional the centre and pain-body are additional concepts to the egotistical false self the authors describe. But the concepts are closely connected, as the emotional part operates in tandem with one’s false sense of identity. For example, negative reactions may occur to defend and uphold the egotistical self-image we cling to and identify with so strongly. According to the authors, both of these psychological attributes must be observed and seperated from and eventually dissolved.[61]

Nicoll draws a connection between how the negative emotional part operates in people, and their “false personality”—the imaginary “I” or false self that people are “run by” which is “completely imaginary.” [62] The False Personality is said to be formed of mental pictures, fantasies and “imagination about ourselves” that we mistake for who we really are.[63] The False Personality is a primary cause of negative emotions expressed within us.[64] Identification with it inevitably keeps the negative emotional part going, as it makes us “easily offended” because we constantly feel the need to defend our “imaginary self” to ourselves and others, whenever our self-estimation is challenged or “touched”.[65] Nicoll emphasises the need to dissolve or destroy the false personality, negative emotions and the negative emotional part of emotional centre from which negativity is expressed.[66]

Tolle also draws a strong connection between the pain-body and the ego or “false self”—which he describes as a mind-made fictional identity with a “phantom nature” that “runs your life.”[67] The ego to Tolle is “an illusory identity, an image in your mind, a fictitious entity” that’s “created by “unconscious identification with the mind.” [68] “Painful emotions” are “your unavoidable companion when a false sense of self is the basis of your life,” he maintains.[69] And this is largely because the ego constantly feels insecure and threatened by reality and seeks to emotionally defend itself.[70] Tolle associates the pain-body with the egoic false self very directly, indicating the pain-body is “part of” and “cast by” the ego—being its “dark shadow” and more intensified “emotional part”.[71] We can and should entirely “dissolve” the pain-body, ego and the emotional patterns they originate, he indicates.[72]

To Nicoll, one’s False Personality and negative emotional part are also tied up with one’s perception of their past—including any sense of grievance carried. If we are always thinking things are “unfair” with “endless … inner muttering and complaining and brooding,” it creates a “perpetual” sense of “grievance” which is a sign of the “negative part of Emotional Centre working,” Nicoll explains.[73] By living this way we harbour, “long strings of unpleasant memories … that we take as real, as actual, and, in fact, as our past.” These emotional “memories belonging to the negative part of Emotional Centre” act as “chains anchoring us to what we have … [falsely] insisted is ourselves, and defended so uselessly with a useless expenditure of energy.” But we can “separate from” this falsity by seeing that it is not real or truthful. Then one “discards the past as one imagined it to be, and steps right into the present with a certain delight [and] freedom.”[74]

Likewise to Tolle, both the ego and pain-body are intrinsically tied up with one’s perceived past, including any wrongs one believes they have suffered. “If you identify with [the pain-body], you identify with the past,” Tolle writes, and any grievance you carry—which he defines as “a strong negative emotion connected to an event in the sometimes distant past”— will in turn “keep you in the grip of the ego.” If you are strongly “identified with your emotional pain-body” you will have “a whole or a large part of your sense of self invested in it … and believe that this mind-made fiction is who you are.” But you can “step out” of this delusion if you “become present,” he writes. [75]

Eradication

Nicoll and Tolle both present conscious self-observation as the means to break identification with the negative emotional part/pain-body, weaken it, and ultimately eradicate it.[76] Indeed, they present this method as the means to overcome all forms of unconsciousness. This observation should also include the false personality/self and any associated mental-emotional processes.

Nicoll suggests that we observe how “incoming impressions—namely, what people say to you, how they look at you, how they behave towards you—fall [firstly] on False Personality and therefore on the negative part of Emotional Centre” and spur it into action. However, by perceiving consciously in the moment we can “prevent this [process] from happening,” and receive and respond to life’s impressions “consciously instead of mechanically”.[77] This averts the usual process of identification with negative reactions, weakens the grip of our negativity, and brings about an inner transformation in the psyche.[78]

Likewise, because ego identification inevitably brings the pain-body into action —which is the emotional part of the false, unhappy egoic self in any case[79]—Tolle also directs people to observe both egoic thought processes and pain-body reactions, and thereby break identification with these and the suffering they cause. This too is said to bring about a process of inner transmutation.[80]

Nicoll and Tolle both claim that such practice prevents the negative emotional part or pain-body, respectively, from feeding, which diminishes and weakens it. If continued, this can eventually destroy or dissolve it entirely—and one is then free of inner negativity completely. Close and persistent observance of one’s unconscious thoughts and emotions is necessary to accomplish this.

Nicoll, for example, suggests that to be “purified from negative emotions” the negative emotional part must be continually “starved” of the energy it feeds on and “lessened in its power” by continuous self-observation and non-identification.[81] It must eventually be “destroyed in us” this way.[82] To get there, one must observe and go “against negative emotions, by non-identifying with them, not consenting to them, not going with them, not believing them, separating the feeling of ‘I’ from them.” This inner separation prevents one from “feed[ing ] negative emotional part.”[83] One must also observe their habitual thinking so negative thoughts are not identified with and allowed to “infect” the emotional centre and “rouse” the negative emotional part—which will inevitably happen if our thoughts are “unobserved.” [84]

Tolle also suggests we can become free of the pain-body by depriving it of “energy” it feeds on; it can thus be weakened, “transmuted” and ultimately “dissolved.” To do this, one must observe the influx of negativity it brings when it “becomes active”, and stop “identifying with it” so that “it can no longer pretend to be you and live and renew itself through you.” It is vital to “stay conscious” and prevent the “unconscious identification with it,” that “its survival depends on.” This conscious attention must also encompass one’s thought patterns, otherwise it will “renew itself … by feeding on your thoughts” should you identify with negative thinking. But if instead you “observe it directly and see it for what it is” then “the identification is broken” and the pain-body can “no longer replenish itself through you” by “eagerly devour[ing] every negative thought.” Emotional pain, Tolle points out, will be inevitable if the mind is left “unobserved”. [85]

For the reasons outlined above, “the observation of our negative states and the [inner] separation from them is one of the most important sides of practical work,” Nicoll makes clear. This is how one gradually cleanses themselves of the “disease” or infection that is the negative part of emotional centre. Even though “the power of the negative part of the Emotional Centre is terrifically strong” and “difficult to overcome,” its power will nevertheless “be lessened” if it is “starved” of the negative “energy” it feeds on and prevented from taking “the chief place in our emotional lives” by our continual refusal to identify with its activities and feed it. It must not be “allowed to exist unchallenged” and can and “must be destroyed in us” entirely—and the end result will be that there are “no negative emotions” anymore.[86]

Similarly, it is by the conscious process of observance and disidentification that one can become free of the “psychic parasite” that is the pain-body, according to Tolle. However, he indicates that even if you are “no longer energizing it through your identification, it has a certain momentum” that keeps it going for a while, and so “in most cases” it “does not dissolve immediately”—and how fast it does dissolve “depends both on the density of an individual’s pain-body as well as the degree or intensity of that individual’s arising Presence.” But it nevertheless weakens and “begins to lose energy” from being prevented from replenishing itself, and as this happens one’s “thinking ceases to be clouded by emotion” and it “cannot then take you over” as readily as before. Yet ultimately it is possible to reach the point where “your presence is intense enough to have dissolved the pain-body” entirely. He claims “love cannot flourish” fully until this is accomplished.[87]

There are some differences on this point however. Nicoll is very insistent about the difficulty of this work: “The inclination to be negative is very difficult to overcome and we are foolish if we think otherwise.”[88] However, Tolle is much more vague and contradictory, suggesting in one place that the pain-body is nothing but “an insubstantial phantom that cannot prevail against the power of your presence.” Yet elsewhere he seems to suggests, as mentioned, that it does actually prevail for some time “in most cases.”[89]

So, “How long does it take to become free of the pain-body?” In A New Earth, Tolle seems to make an attempt to answer this question, which he admits people “frequently ask” him, but sidesteps the central issue. The answer he gives is: “it depends both on the density of an individual’s pain-body as well as the degree or intensity of that individual’s arising Presence.” He then shifts the focus by pointing out people can start disidentifying now so that “transmutation begins” —but without addressing how long or difficult the ensuing process is. In effect, he bypasses the question by telling people to just accept themselves as they are “with or without the pain-body.” [90] There seems to be an inherent contradiction in a teaching that stresses the importance of transmuting and dissolving the pain-body for love to flourish, yet tells people to just accept having one when they seek specifics on the process.

The apparent contraction in Tolle’s messaging here could suggest that he has been influenced by, and incorporates, sources with fundamentally different views of, and approaches to, enlightenment—and has not consciously recognised or reconciled this in his worldview or messaging. I have discussed this possibility before.[91]

There is also an ethical matter worth briefly considering here as well. Tolle is selling products and services that seem to suggest, if not outright promise, that emotional negativity can be completely dissolved by applying his present-moment methods. He has become a multi-millionaire on the back of his teachings and tends to charge rather high tuition fees for his public appearances. [92] Given this, I think it would only be fair to provide, at the very least, some clearer, detailed information on how his method to dissolve all negativity is supposed to work in practice for most people who apply it, how the process unfolds toward that outcome specifically, and what one can realistically expect.

But let’s return to how Tolle’s concept differs from Nicoll in this area.

Another conceptual difference is that the negative emotional part is said to be acquired in this life under external influences in childhood, according to Nicoll, while Tolle surmises that the pain-body is already inherited prenatally from the “collective pain-body of humanity”[93] which “is probably encoded within every human’s DNA”.[94] However, it subsequently grows and develops under the negative influence of others in childhood in much the same way nonetheless.

Yet the time-body, which I discussed earlier, does have a prenatal existence also. Nicoll incorporated Ouspensky’s views about the recurrence of our lives and implies we continue with our time-body from one life cycle to the next. He suggests if we transform and change our time-body now in this life then “things are different” when we “re-enter … life at the moment of birth” such that “in recurrence you will meet your more conscious self, as it is now”—but if this change does not occur then “life recurs just as before.” [95] So the time-body is not a blank slate at birth but already affected by its state from previous life cycles—and will presumably attract more suffering in future cycles too if its present state remains unchanged.

While Tolle’s pain-body finds much in common with Nicoll’s work, the similarities are often even starker when compared to the work of Barry Long, whom he actually met in person. In Long’s work, as we shall see, much that Nicoll conveyed across the two concepts we’ve examined—the time-body and negative emotional part—converges into one: the “emotional body”.[96]

The “Tantric Master” Barry Long and Eckhart Tolle’s Pain-Body

Tolle’s portrayal of the pain-body as a quasi-possessing entity lodged within, consisting of accrued emotional suffering, is close to identical to a concept presented by the Australian author and teacher Barry Long.

A former newspaper editor and parliamentary press secretary in Sydney, Long abandoned his career and family to travel to India in 1964 in search of enlightenment. He later claimed self-realization status and began teaching independently in Highgate, London in the 1970s.[97] Tolle states that he “spent some time with Barry Long” here before his own teaching career began. [98] Tolle frequented Long’s Highgate sessions for sometime during the early to mid 80s.

Long initially taught small groups and released written material in pamphlets and leaflets. By the 1980s and 90s he was travelling widely across the globe delivering seminars, a number of which were recorded. He published numerous articles and dozens of video and audio recordings. Much of this material was later reused in books, some published posthumously; he ultimately authored nearly twenty.

Long returned to Australia in 1986 and continued teaching until his death in 2003. While he made a mark on the new age scene and garnered an international following, he never attained the fame and eye-watering book sales Eckhart Tolle later did. It’s unlikely he sought this, as he embraced positions which, as a former media professional, he must have known had no chance of cracking the mainstream. Sometimes he was even too much for the more alternative scene he occupied: one article he submitted to a New Age magazine was deemed too controversial to publish.[99]

Long openly declared himself a “tantric master”[100] and ran a full page advert in London newspaper The Observer with his picture and the bold message beneath: “I am Guru. Who are you?”[101] His writing covers territory as varied as lamenting the global rise of representative democracy to describing the afterlife passage through hell. Long could be provocative and uncompromising in his views, whereas Tolle, in contrast, navigates less controversial self-help territory, with a wider appeal.

While Long’s work covers a far broader scope of topics than Tolle, his central focus still accords closely to the practical psychological teachings of the Fourth Way that Tolle’s message also shares so much in common with—namely, practicing present-moment awareness for self-knowledge and inner change.

So who were Long’s influences? Long, much like Tolle and some other New Age figures, considered his own teachings “original” in the sense of being derived from his personal experience, insight or “gnosis.” [102] Yet, also like Tolle, there are figures he acknowledged, spoke highly of, or whose influence appears evident in his writings.

Long acknowledged being inspired by Jiddu Krishnamurti, who he mentions a number of times in his writings, and suggested his teaching “owes much” to his influence. [103] [104] He also spoke highly of Ramana Maharshi. According to Long’s publisher, these Indian teachers, among others, were “respected and publicly acknowledged by Barry Long”.[105] The same are also highly regarded by Eckhart Tolle, who claims his message is “at One” with theirs.[106] Indeed, the term “stillness,” favoured by Long and Tolle, finds prior, though by no means exclusive, usage in J. Krishnamurti’s and Ramana Maharshi’s work, although neither used it as centrally and extensively as Long and Tolle later did.[107]

So what about Long’s familiarity with the Fourth Way itself? We know that Gurdjieff “inspired” Long’s “early spiritual self-enquiry” according to his long-time editor.[108] Long also described Gurdjieff’s teaching as “admirable.”[109] One biography notes that Long’s message “owes a lot to the practicality of the Gurdjieff Work.”[110]

While we’re on the subject of Krishnamurti and Gurdjieff, it’s worth briefly noting that that the German-American endocrinologist Harry Benjamin proposes that, “in the writings of Dr Nicoll … lies the bridge that links the work of Gurdjieff with that of Krishnamurti.” He makes this claim in Basic Self-Knowledge—an introduction to Gurdjieff’s teaching based largely on Nicoll’s commentaries, with some reference to Krishnamurti. He goes so far as to claim, “In the Commentaries of Nicoll as in the teachings of Krishnamurti, we can again be shown the way to tread again the very same path, and with identical results.” This path is “exactly the same way as depicted by Christ in the Gospels” toward “the Kingdom of Heaven” within.[111] I think it’s certainly true that there is much in common between Nicoll and Krishnamurti, but it’s going too far to suggest they taught the “very same” approach. There are significant, fundamental differences—but that is beyond the scope of this essay to discuss. I’ll just say for now that where differences in approach do exist, both Long and Tolle follow more closely to the Fourth Way approach than to Krishnamurti’s. [112] I raise this now just to highlight the complex interconnected weave of influences we are dealing with.

Those familiar with the Fourth Way would indeed recognise some clear similarities between Long’s message and “The Work” in any case (and the same is true with Tolle’s message). For example, Long emphasises observing negative emotions and the falsities of one’s personality with conscious awareness in the present moment, and ceasing to identify with these aspects within, in the circumstances of ordinary life.[113] This is one of the central psychological premises of the Fourth Way system and was elaborated at great length Nicoll. It is clear enough to me that Long’s work owes something to that system.

This is apparent in the concept we now turn to. For while Long’s description of the “emotional body” or “unhappy body … composed entirely of … painful emotional material” is much the same as Tolle’s “emotional pain-body,” it also shares nearly all the same similarities with Nicoll’s work as Tolle’s does, which we looked at earlier.

For anyone diving into Fourth Way literature in the early 60s, when Long began his spiritual search, there was far less written material available than now. Nicoll’s five volume Psychological Commentaries was by far the most extensive and comprehensive exploration of the practical psychological side of the system in print (and probably still is). Given Long’s familiarity with Gurdjieff and the Fourth Way, it stands to reason that he could have come across Nicoll’s commentaries at some point, which, as we’ve seen, expound, and in some cases expand upon, ideas about the inner workings of emotional negativity first broached by Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. However, it’s also possible that any Fourth Way influence on Long was minimal or far more indirect, and Long developed his own concepts to explain the same, observable psychological phenomenon that Fourth Way teachings address from a similar, though slightly different, angle—and these explanations happen to converge.

Whatever the case, viewed from a purely literary perspective, it is in Nicoll’s work, published in the early 1950s, where we find all the relevant precursors, in print, for certain ideas Tolle would popularise much later.

To summarise, there are key parallels across the work of Nicoll, Long and Tolle around the idea of a psychic component that carries, expresses and feeds upon emotional negativity and suffering. The key aspects of this idea can be summarised as follows:

- Emotional negativity/unhappiness is something unnatural in the human psyche[114]

- It is absorbed (either partly or entirely) through the external influence of other people and one’s environment while growing up[115]

- This develops an unnecessary psychological apparatus that generates further negative emotions and is fed by their energy

- The emotional suffering, pain or negativity accrues in an invisible psychological body of some kind

- This body/apparatus (and all negative manifestations) must be observed, not identified with, and thereby transformed/transmuted

While the first three points are more typical of the Fourth Way doctrine, the last two, particularly with respect to the time-body, are idiosyncratic of Nicoll’s writings incorporating Ouspensky’s ideas into the system. As far as I can tell, Nicoll’s work was the earliest literary source where all components of this idea appear together.

The congruence between the three authors on these points strongly suggests the possibility, at the very least, that the latter writers were familiar with how their forerunners expressed them. While this may be debatable with Long, I don’t believe it is with Tolle. The similarities he shares with both Long and Nicoll are difficult to explain as mere coincidence. It is not just that Tolle discusses similar or equivlanent ideas; he at times employs similar phrasing to express them too.

However, as we have seen, while Nicoll uses two distinct concepts to cover this ground—a psychological “body” filled with negativity which must be transformed and a negative emotional part fed by and expressing such negativity which must be destroyed—in Long’s work these attributes coalesce into one concept for the first time: a psychological body accumulates negativity, is fed by and expresses this negativity and must be dissolved.

The terminology may vary slighlty (unhappy body vs pain-body), but Long provides essentially the same conceptual model Tolle’s pain-body is based upon.

This commonality has not escaped the attention of Long’s publisher. The Amazon description of his book Only Fear Dies: A Book of Liberation includes the following statement: “written 15 years before Eckhart Tolle’s world best-seller ‘The Power of Now’, Barry Long’s book covers similar ground and has been hugely influential.”[116] This statement is hardly cryptic. And indeed this book, in which Long describes the “unhappy body” or “emotional body,” certainly does cover similar ground to Tolle’s later work.

Although published in its current form in 1994, Only Fear Dies is a revised and extended edition of Ridding Yourself of Unhappiness (1984), with additional essays originally published as audio-tapes incorporated (two in 1985 and one in 1993). While Long covers varied topics such as media, politics, and life after death, he mainly explores the psychological causes of unhappiness and how to overcome these to reach enlightenment. Long states the text will enable readers to “develop to a certain stage of consciousness,” and was written “to expose your unhappiness and show you how you can start to dissolve your own emotional body.” He describes a “process of getting rid of the unhappiness that has accumulated in you.”[117] And on this theme at least he finds much in common with Nicoll and Tolle.

Another book of note is The Way In: A Book of Self-Discovery. Long’s publisher describes it as “the best survey of the practical aspects of Barry Long’s teachings.”[118] Although first published in its current form in 2000, it is largely based on earlier chapters, leaflets, statements, letters, and audio books, many with their genesis in the late 1970s and 1980s.[119] It deals with many related psychological and spiritual topics, but the most relevant here is his description of the emotional “pigmy” carried within. This is essentially another name for the “emotional body” or “unhappy body” mentioned above—the concept is identical. For the purposes of my comparison to Tolle’s pain-body, I treat Long’s statements about the emotional/unhappy body and pigmy as one concept under different terms.

It’s worth noting that Long also conveys the more common notion that we have a “false self” or “false nature”[120] that we mistake for who we really are—a delusion producing suffering. He often calls this the “personality” (among other terms) and repeatedly describes it as a psychological “mask”—a metaphor found in the Fourth Way. The sense of “me and mine” and of “likes and dislikes” are core to its functioning—points Tolle would later reiterate, along with the idea that it thrives on “habitual unconsciousness,” and compulsive thinking. [121]

And as with Nicoll and Tolle, to Long this false identity is closely entwined with an additional emotional component. In Long’s case, this is the unhappy/emotional body, or pigmy. I should note, however, that because these psychological aspects are so closely related, sometimes the conceptual line between the false self and emotional/pain-body is blurry in the work of Long and Tolle.

I’ll now compare how Long’s version of this idea of the emotional body corresponds to Tolle’s pain-body, and outline the many ways they closely align.

The emotional parasite within

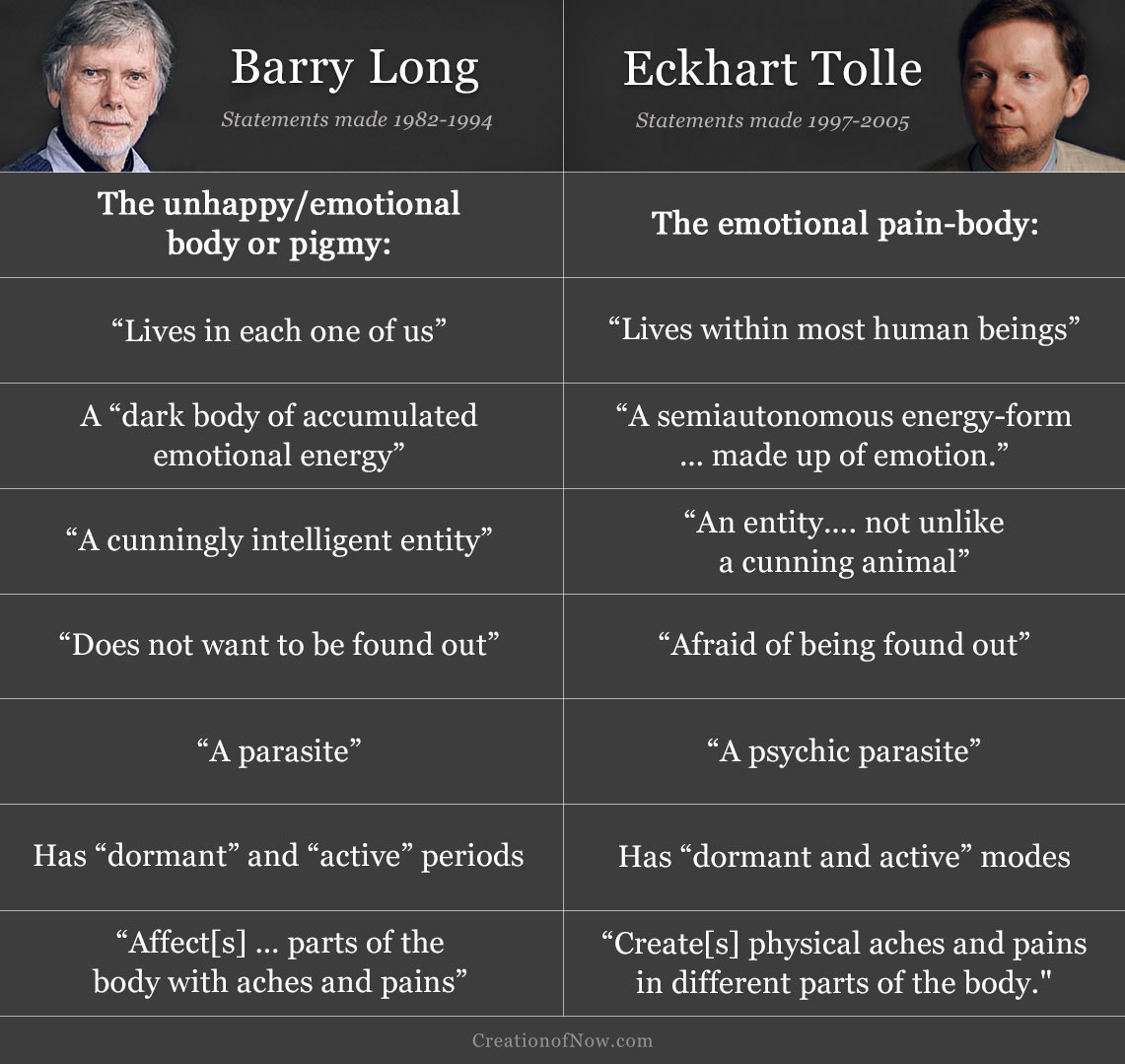

Long and Tolle similarly describe the emotional-body or pain-body respectively as energetic parasitic entities consisting of accumulated emotional pain, producing and feeding on negative states, and harming us psychologically and physically.

Long presents the unhappy/emotional body as being formed of “painful emotional material” and suggests “all the unhappy moments of your life live on” in it. He similarly describes “the pigmy” as a “dark body of accumulated emotional energy” which is “the living past in you”. This body of painful emotional substance is “not natural”, and “is responsible for all your negative moods” which serve to sustain it. Under its influence a person becomes “addicted to … emotional pain or unhappiness.” [122]

Tolle similarly describes the pain-body as a “semiautonomous energy form” comprised of the “residue” or “remnants” of “accumulated pain” left behind by “every strong negative emotion” which “join together to form an energy field” that “occupies your body and mind.” This “emotional pain-body”[123] is “the living past in you.” It gives rise to negative emotions fundamentally unnatural in a person, which feed and renew it, and its presence underlies humanity’s “addiction to unhappiness.”[124]

To both authors, this “entity” is a living thing bent on survival. It wants to remain unseen and unrecognised for what it is—a parasite we could do better without.

Long describes the emotional body or pigmy as a “living thing” that “lives within each one of us,” yet is fundamentally “separate” from one’s true nature. This “cunningly intelligent entity” with independent will and agency is “as alive and intelligent as you are.” As a consequence it wants to preserve its existence; it “will not surrender,” “does not want to die,” and “does not want to be found out and seen as separate from you.” [125]

Tolle likewise describes the “emotional pain-body” as “an invisible entity in its own right,” which “lives within most human beings.” It has “its own primitive intelligence, not unlike a cunning animal” which is “directed primarily at survival.” Because it “wants to survive, just like every other entity in existence,” it is “afraid of being found out” because it “can only survive” by your ongoing “unconscious identification with it.”[126]

This “living thing, living off you,” is “a parasite,” according to Long, since it “feeds off” a person emotionally. He also calls it “the parasitic emotional body” and describes unhappiness as “parasitic.” Long suggests the unhappiness living within actively feeds upon one’s own negative emotions as well as that of others around them, such as family members, and will live off “any emotion at all” that can “satisfy and nourish it.” This causes an enormous loss of energy, Long suggests, as people are “dissipating” their “energy”. The emotional body has a detrimental impact on health: it is “health-eroding” and “degenerative,” and creates various “aches and pains.” [127]

Tolle also describes the pain-body as a “psychic parasite”—a “life form” that “periodically needs to feed.” This “parasite” can “live inside you for years” and “feed on your energy” and “any emotionally painful experience can be used as [its] food.” A person under its influence will also “feed on [the] negative emotional reactions” of those around them, such as family members. All negative emotions and thoughts cause a “serious leakage of vital energy,” according to Tolle. The pain-body can create “physical aches and pains” and its rampant feeding leads to “a depleted organism and a body much more susceptible to illness”.[128] [129]

Development in Childhood

Long writes that a person is born with an initial quantity of “unhappiness” or negative emotion, transferred from the mother during gestation. This emotional unhappiness is the underlying “substance” the unhappy/emotional body is formed of. After birth, unhappiness continues to “enter and grow” in a person, and a “ball of past pain” accumulates within. This forms the emotional body, which develops further as the person matures. It incorporates “every single hurt of your childhood,” and all painful experiences throughout life continue to add to it. [130]

Tolle writes that each person “who comes into this world, already carries an emotional pain-body” and that in some babies “it is heavier, more dense than in others.” After birth, the pain-body continues to grow and develop by incorporating “every emotional pain” you experience—this includes all “the pain you suffered as a child.” Each negative emotion “leaves behind a residue of pain that lives on,” merging with “the pain of the past,” and causing the pain-body to grow further.[131]

The authors make similar points about how parents can raise children in ways that reduce the strength and growth of unhappiness in a child.

Long suggests parents help their children consciously recognise and separate from emotional unhappiness at an early stage in life. A parent must first of all “consciously face the emotion” in their child with “pure presence” when the child has a strong emotion. Later, when the child is “still and receptive,” the parent can explain to them the underlying nature of their unhappiness. The goal, he explains, is to help the child “see the invader for what it is – something separate from itself.”[132]

Tolle likewise suggests that parents help their children become detached from the pain-body at an early stage in life. A parent must “stay present” and not be “drawn into an emotional reaction” when the child has a “pain-body attack.” Later, once the emotion has subsided, the parent can talk to the child and ask questions “designed to awaken the witnessing faculty in the child, which is Presence.” Through this process parents can help the child to “disidentify from the pain-body.” [133]

Facing and dissolving the Psychic “entity”

Long and Tolle provide similar strategies on how to observe, deal with and eventually dissolve the emotional/pain-body. The approach pivots on maintaining awareness in the present moment and observing its activities as they happen without identification. In this way, one can stop adding to their emotional/pain-body, decrease the psychological load of unhappiness one carries, reduce the strength of this parasitic entity, and eventually rid themselves of emotional negativity altogether.

Long suggests one needs to “stay in the present” and “perceive the fact” when experiencing any event, and see life “only as it is” without analysis or interpretation. In this way you can “prevent the emotion of the moment from entering you.”[134]

Tolle indicates you can stop “creat[ing] pain for yourself” and prevent the re-emergence of “past pain” if you “realize deeply that the present moment is all you ever have” and avoid “unconscious resistance to what is.” Every emotion that arises should be “fully faced, accepted, and then let go of” which prevents it from adding to and renewing the pain-body.[135]

One must also pay heed to their arising thoughts as well as emotions, both point out, as these pain entities also manipulate you through compulsive thinking.

Long states that, “its main distraction is to make you think,” as “thinking will…stop you from getting at the root of the emotional body.” If you “stop thinking,” he explains, it is “practically homeless.”[136]

Tolle writes: “the moment your thinking is aligned with the energy field of the pain-body, you are identified with it and again feeding it with your thoughts” and, consequently, “once you have severed the link between it and your thinking, the pain-body begins to lose energy.”[137]

Both draw attention to the pain entity’s “active” and “dormant” cycles when it has more or less activity, power and influence.

Long makes clear that the emotional body passes through “dormant” and “active” phases. When active it produces strong emotions and you can very easily “become identified with it, absorbed by it and lose yourself in it.” For this reason, he suggests that people learn to recognize it when it’s “just dormant [and] ticking over” in order to “begin to deal with it” when it’s not “rampant and active” and its influence is not so overwhelmingly powerful. [138]

Tolle also suggests the pain-body has “two modes of being: dormant and active.” When the pain-body is “triggered” into action, a person may easily “become identified with it,” which leads to “deep unconsciousness.” For this reason, he encourages people to “bring more consciousness into…life in relatively ordinary situations, when everything is going relatively smoothly.” Dealing with commonplace “ordinary unconsciousness” makes it “much easier to deal with deep unconsciousness” when it arises.[139]

Long describes a psychological process to “dissolve the emotional body,” or pigmy and rid oneself of negative emotions entirely. He states that it is “stillness” (also variously described as “conscious awareness,” “conscious attention,” and “presence”) that has the power to do this and emphasises that “now, this moment, is always where you begin,” a notion he later contrasts to the “delusion” that “freedom…can only be achieved in time” and “not now.”[140]

According to Long, first one should “focus…inner attention on the feeling in the area of [the] navel” – “holding the sensation with your attention” and “feel” any emotion within. “The surface of your emotional body can be felt now,” in this way, he suggests, which means “feeling the actual feeling, the physical sensation, inside your body.” One should “look, energetically” and “sink into that feeling” to “become the feeling” but “without thinking” or “draw[ing] conclusions,” and continue “being still” and holding the “spotlight” of your “searing conscious attention” upon it. [141] Although “to dissolve the emotional body … is a big job,” Long claims that if a person is focused and still, they can gradually overcome and dissolve it and negative emotions with the power of their conscious attention or awareness.[142]

Tolle also describes a method for “dissolving the pain-body,” a process that can permanently remove all accumulated emotional pain within. He states that it is “conscious presence” (also variously described as “Awareness,” “conscious attention,” and “presence”) that has the power to do this and emphasizes that “you can only be free now” and that “presence is the key to freedom,” as there is “no salvation in time.”[143]

To proceed, first one should “focus attention on the feeling inside” by “putting the spotlight of your attention on it.” One should “know that it is the pain-body” and “hold the knowing” and “be the knowing; that is to say, be aware of your conscious presence and feel its power” while feeling the pain-body within. One should “feel its energy directly,” “accept” the feeling but without “thinking,” judgement, or analysis—acting as a “silent watcher.” When “your presence is intense enough to have dissolved the pain-body” then love can flourish within. But in most cases it “does not dissolve immediately” but gradually loses energy as it is “transmuted into presence.”[144]

A point of difference to note, however, is that Long emphasises meditation practice in addition to self-observation in daily life. Formal meditation is given comparatively little emphasis by Tolle.

Comment on the similarity

The similarities I’ve outlined make it very clear that Tolle’s signature pain-body concept shares much in common with the work of Nicoll and Long. It appears that Tolle’s work owes much to Nicoll and Long in this respect—although the apparent influence does not end there.

Given the similarities are deep and manifold, the question must be asked: why is this fact not widely recognised? Why is Eckhart Tolle’s pain-body generally regarded as an original idea in the public consciousness when it already existed in other teachings, albeit under other names?[145]

As mentioned before, this can be explained by the fact that Nicoll and Long are obscure figures to most. But then another question arises: if this public perception persists, why has Tolle allowed it to? Why has he not clearly and plainly acknowledged any debt or gratitude to others with respect to this concept?[146]

On one occasion when taking questions at a seminar, an audience member raised the commonalities between Barry Long and Tolle, and expressed admiration for both. He even made direct reference to “the pigmy and pain-body”. Tolle listened quietly and began nodding profusely when Long’s name and Tolle’s history with him was mentioned. The questioner ended by saying, “I just want to know what the influence or the conversations and dialogues were.” As soon as the word “influence” was spoken, Tolle made abrupt but polite attempts to cut him short and respond.

But the question was not answered. Tolle spoke about how he met Long and “loved” his teachings and admired him—which he has done before when asked—but made no comment on how Long may have influenced the content of his work. He praised Long but avoided the substance of the question.[147]

When Tolle writes of the pain-body in his books, he makes no attempt to attribute the concept itself—either to Long’s or to Nicoll’s presentation of related ideas.

In an interview with Marie Benard from Namaste Radio in 2010, Tolle seems to suggest that he discovered the existence of the pain-body in people independently.

The pain-body is an energy field … almost an entity, that consists of accumulations of past emotional pain or suffering…. It is an energy form—I’ve, through working with people, I came to that realisation that people carry inside—some to a greater extent than others—people carry inside this energy field that thrives on drama and unhappiness [chuckles]. And that was quite a realisation for me when I saw that people got periodically taken over by that entity. [Emphasis added] [148]

Tolle states he “came to that realisation” that people carry a pain-body inside by working with them and that it “was quite a realisation” for him to see that. But given his known early contact and familiarity with Barry Long, whose teachings he “loved,” and, considering the commonalities his “realisation” shares with Long’s perspective, it is difficult to believe that Tolle spontaneously came to this independently.

And that is to say nothing of the many commonalities Tolle’s message shares with Fourth Way teachings as well, which are likely to have had some influence on Long too for that matter. [149]

Further into the same interview, Tolle discusses what occurs when “the pain-body links into the sexual centre.” In such cases “pain is experienced as pleasurable” and “there’s a pleasurable sensation in the sex centre” in connection with some form of physical or emotional pain.[150] This is reminiscent of Gurdjieff’s dialogue on the abuse and abnormalities arising when “the sex center unites with the negative part of the emotional center or with the negative part of the instinctive center.” The result is that sexual stimulation becomes intermingled with “unpleasant feelings and unpleasant sensations.” [151]

Those familiar with Gurdjieff’s work would recognise that Tolle used Fourth Way terminology here. The “sex centre” is one of five “centres” Gurdjieff ascribes to different human functions: thinking, feeling, moving, instinct and sex.[152] Tolle’s repeated reference to the sex centre in this interview strongly suggests he is familiar with this system, or by others influenced by it. The same can be said for his claim that the pain-body can link into the sex centre, much as the negative part of the emotional centre, discussed earlier, is said to.

Of course, with respect to the Fourth Way, there are many other commonalities I have already highlighted in Nicoll’s work, such as how Tolle’s claim that we marry our partners pain-body mirrors Nicoll’s claim that we marry our partners Time-body—with similar adverse results if they are too negative.

The pain-body is merely one of the most notable concept to analyse in showing Nicoll’s probable influence upon Tolle’s work (in this case, alongside Long, whose influence on Tolle on this point is even more apparent). There are many other signs of influence I could mention.

For example, Tolle reiterates Nicoll’s refrain that “sin means to miss the mark.” Nicoll explained that the Greek word in the Gospels translated as “sin” literally means “to miss the mark” and “was used in archery, when the target was missed.” Therefore to sin really means to miss “the very idea of … existence” and its deeper purpose and aim—which is inner “transformation” and “awakening … becoming more conscious.”[153] His posthumous book The Mark is named after this idea, but he also made the point in his commentaries. The same point is made by Tolle in A New Earth: “sin means to miss the mark, as an archer who misses the target, so to sin means to miss the point of human existence.” And, like Nicoll, Tolle sees the real purpose of life as the “awakening” or “transformation of consciousness.” [154]

Nicoll uses the term “inner talking” to describe the mental “monologue” going on in people that’s typically “negative in character”—“a stream of mechanical inner talking and phantasy goes on endlessly” which they strongly identify with. He compares it to people who “go along in the streets muttering to themselves” and suggests the same process goes on inwardly in us “all the time” only it “is not expressed outwardly”.[155]

Tolle uses the term “the voice” to describe much the same thing: the inner mental voice or voices that go on in one’s mind as “continuous monologues or dialogues”. This “incessant stream of thinking” has a mostly “negative nature,” and people unconsciously identify with it. He also cites the case of “people in the street incessantly talking or muttering to themselves” and adds that “the voice” in our head is not much different, we just “don’t do it out loud”.[156]

I’ve already noted elsewhere how Tolle makes reference to the horizontal and vertical arms of the cross representing time and eternity respectively, with the intersection point being the present moment where the timeless dimension can be accessed within. This mirrors a point repeatedly made by Nicoll, accompanied by diagrams, in his Psychological Commentaries. When elaborating this idea—only briefly touched upon in his books—in a webinar with Oprah Winfrey, Tolle made clear he knows other people express this notion.

A few people have interpreted the Christian cross … as … showing the horizontal dimension of life, and suddenly it intersects with the vertical dimension.[157]

These people are left unnamed.

Concluding Comments

This brings us back to the question raised earlier: if Tolle was influenced by Maurice Nicoll and Barry Long, why hasn’t he clearly acknowledged them? In his “Acknowledgments” at the end of The Power of Now, Tolle expresses “love and gratitude” to his unnamed “spiritual teachers.” [158] But can there be genuine gratitude without attribution?

In the introduction to the same book Tolle claims that his teaching “is not derived from external sources, but from the one true Source within.”[159] I find that statement difficult to reconcile with the evidence I’ve raised in this and previous essays.

Understanding the truth of an idea is not the same thing as originating it. Why wouldn’t Tolle simply express gratitude for the ideas, terms, concepts and practices derived from earlier sources that he saw fit to incorporate into his worldview and work? He has nothing to lose from doing so, except… what? I’ll leave that for the reader to ponder.

While it is beyond the scope of this essay to attempt to explain Tolle’s apparent reticence on this matter, one thing seems plain to me: the evidence I’ve presented makes it clear enough, at least in my reckoning, that two teachers who did significantly influence Tolle were Maurice Nicoll and Barry Long.

Nicoll expressed key characteristics underlying the pain-body concept within one literary work, albeit over two distinct but related concepts. This was an extremely influential development. In Long’s works the elements converge in one concept, and it’s his conceptual model Tolle uses. Whether Long developed his concept of the unhappy/emotional body entirely independently, or with some influence from Fourth Way ideas (and to what degree) is open to debate. But what does seem clear to me is that both of these earlier authors significantly influenced how Tolle presents the concept of the pain-body, among other things.

Nicoll and Long’s influence on Tolle is, I believe, far greater than other figures Tolle chooses to mention in his writings, like J. Krishnamurti or Ramana Maharshi.[160] But in spite of going unmentioned in Tolle’s books—or, perhaps, because of this—their influence is far more apparent and conspicuous when a deep analysis is carried out. I believe that without either of them, the Eckhart Tolle phenomenon simply would not be.